Success, or failure, in business is the result of the management of a great many forces which bear upon an organization. One role of executives is to manage these forces, anticipate change, and steer the organization and its business units in the direction that best serves the institution’s mission and its stakeholders.

To do that successfully, it is my opinion that executives need five basic management competencies. Not all executives are good at all of these competencies, in fact, most have strengths and weaknesses like any professional person. But executives have been elevated to high positions most likely because they possess all or most of these in some measure.

Risk Management

I have come to believe that perhaps one of the most essential skills of the successful executive is the management of risk. The skill of risk management extends beyond the silos of business practice. CFOs must understand and mitigate financial risks to organizations, while CIOs manage risks related to information technology systems and data. Executive boards must seek out evidence that executives know and understand the risks to an organization, and that they are actively managing those risks using the best available practices.

Relationship Management

This one has many names. Daniel Goleman’s “emotional intelligence” may fit here. The competent C-Suite executive must be able to manage a variety of relationships – with employees, colleagues, board members, vendors, shareholders, creditors, donors and the public. Success in relationship management doesn’t mean making all of these people happy all the time, but it does mean earning their respect for having the ability to understand each of their unique perspectives, and weaving these into the fabric of the business in a way that “raises all ships”. When these relationships are not well-managed and they get out of balance, businesses fail.

Money Management

As I built this list, I asked myself if this one should be “resource management” instead. After some thought, I think not. Money is the resource that matters. Money is the tiller that steers the organization. Better yet, it is the thrusters. Too much thrust on one side of the ship can send it careening off into space. Money is the road to finding efficiencies, and inefficiencies. Every manager should be able to balance a budget, but a C-suite executive should be a “spreadsheet whisperer”. Managing money is about more than the bottom line. It is understanding the power of money and where to best apply it, or remove it.

Time Management

I once worked for a senior executive who was incensed by email responses that were non-essential. For instance the “OK, Thanks!” or “I will check on that and get back to you”. He had determined that these types of emails were a significant drain on his time. They added to his email inbox and he had to deal with them, yet they had little value. He knows you are thankful. He knows you will check on it, that’s what he just asked you to do and that is your job. The C-suite exec should pay attention to time management. There is, after all, only so much of it. Is this blog post too long?

Crisis Management

I once worked with a Chief Security Officer from the Southern United States – the great State of Georgia. He used to say that his job was to protect his organization from “the acts of Satan and the laws of Murphy”. I always admired his ability to so succinctly articulate his role in the organization. I recently finished a research project on the perceptions of readiness for cybercrises by C-suite executives in IT. Most thought they were ready, but empirical evidence showed otherwise. The entire C-suite should have a plan and a system for managing crises. They will come, some say in ‘threes”. That is one of the Laws of Murphy.

I may write about these individually at some point. But this post serves to document what I believe are “Five Essential Management Skills” for C-Suite executives.

As fires burn at critical infrastructure facilities in Saudi Arabia, a striking new link between Yemen and drones (which may prove to be a ruse), continues a story that has been developing for years, and reminds those who care about homeland security that we are watching the development of new capabilities that are likely to have an impact far beyond the Arabian Peninsula.

While a proxy war has been continuing in Yemen between Iran-backed Houthis and the US and Saudi-supported Yemeni government, rebel groups have been honing their skill at turning recreational and commercially available drone technology into weapons of war. I think it is interesting that the refinement of this dangerous new tool of terror is taking place in a country where, nearly a decade since, the United States flexed its remote controlled muscles, using drones to kill several members of the al-Awlaki family, including at least two American citizens and multiple children, the most recent of which was killed in January of 2017 under the Trump administration.

Yemen has long been a base of operations for terrorist activity. The collective memory, as it fades with the passage of time, might forget the bombing of the USS Cole in October of 2000, which followed an earlier attempted attack by Al-Qaeda on the USS The Sullivans in January of 2000. Both of these attacks took place in Yemen’s Aden harbor and had connections to Yemeni and Saudi terrorists, some of whom went on to take part in the attacks of 9/11.

More recently, following the mass shooting at Fort Hood, Texas by Nidal Hasan, it emerged that Hasan had connections to Yemeni-American Anwar al-Awlaki. al-Awlaki continued to emerge as connected to a number of attempted attacks, including the 2009 “Underwear Bomber” and its perpetrator Umar Farouk Abdulmuttallab who told investigators that he was trained by al-Awlaki, who had moved to Yemen in 2004. By 2010, following a number of documented statements by al-Awlaki supporting al Qaeda, al-Awlaki was named a member of Al Qaeda by the United Nations, and became Terrorist #1 in terms of threat and a target in the ongoing war on terrorism.

In September of 2011, ten years after the 9/11 attacks, Anwar al-Awlaki was killed by a Reaper drone in Yemen. Also killed in the attack was Samir Khan, another American citizen. According to a 2013 article in the New York Times, al-Awlaki’s killing marked the first extra-judicial killing of an American citizen as an enemy in war by the American government since the Civil War. But that wasn’t the end of the story.

Just two weeks later, the US conducted another drone operation that resulted in the deaths of Anwar al-Awlaki’s 16-year old son, Abdulrahman, and his 17-year old cousin as they sat at an outdoor cafe in Shabwa, Yemen. That drone operation also killed 8 other people.

The US was also responsible for the death of Anwar al-Awlaki’s 9-year old daughter, Nawar, who died during an attack by special operations personnel in Yemen in January of 2017.

Since the drone operations conducted by the American forces targeting Anwar al-Awlaki and others in Yemen, rebels within Yemen have apparently been building a drone capability of their own. In January of 2019, Houthi rebels claimed responsibility for what has been called the first successful assassination using a drone operated by a non-governmental entity. Operators used a drone laden with explosives to attack a military parade at an air base near Sanaa, Yemen, killing two officers and six soldiers, including the head of Yemen’s intelligence unit.

Now, the Houthi rebels have taken responsibility for a major attack on Saudi oil facilities, which they have tried before with less success. While it may emerge that Iran or others were truly at the heart of the attack on Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities, the development of drone technology as a weapon of terrorism bears watching. The equipment used in the attacks known to be the work of the Houthis, that is the January air base attack and 2018 attacks on Aramco facilities in Saudi Arabia and on the Abu Dhabi Airport, is reported to be commercially available technology. And while it may be difficult to obtain such hardware in places like southern Yemen, one only has to order online or run down to the local hobby store in the US. These developments should be on the list of things that keep critical infrastructure security professionals up at night.

We live in a world of radical discontinuity with many demands on our time and attention. It should not be surprising that we lose focus on issues as they enter and then leave the news cycle. There is one issue, however, that should remain a focus of intense scrutiny – that is, interference in elections from hostile nation-states.

This is not the first time that the United States of America has had to work to ensure that our elections are free of hostile influence. During the Civil War, it was widely thought that a coordinated effort was being undertaken to undermine elections in Maryland, Missouri, and other contested states. The concern was that individuals that were fighting on the side of the Confederacy were moving back to their home states in a coordinated effort to sway elections toward candidates sympathetic to the secessionist cause. Various Union Generals argued for the use of the military in an effort to prevent and disrupt enemy influence at the polls. Some Generals, including McClellan, suggested various oaths of allegiance be required, and that arrests of disloyal voters be undertaken at polls.

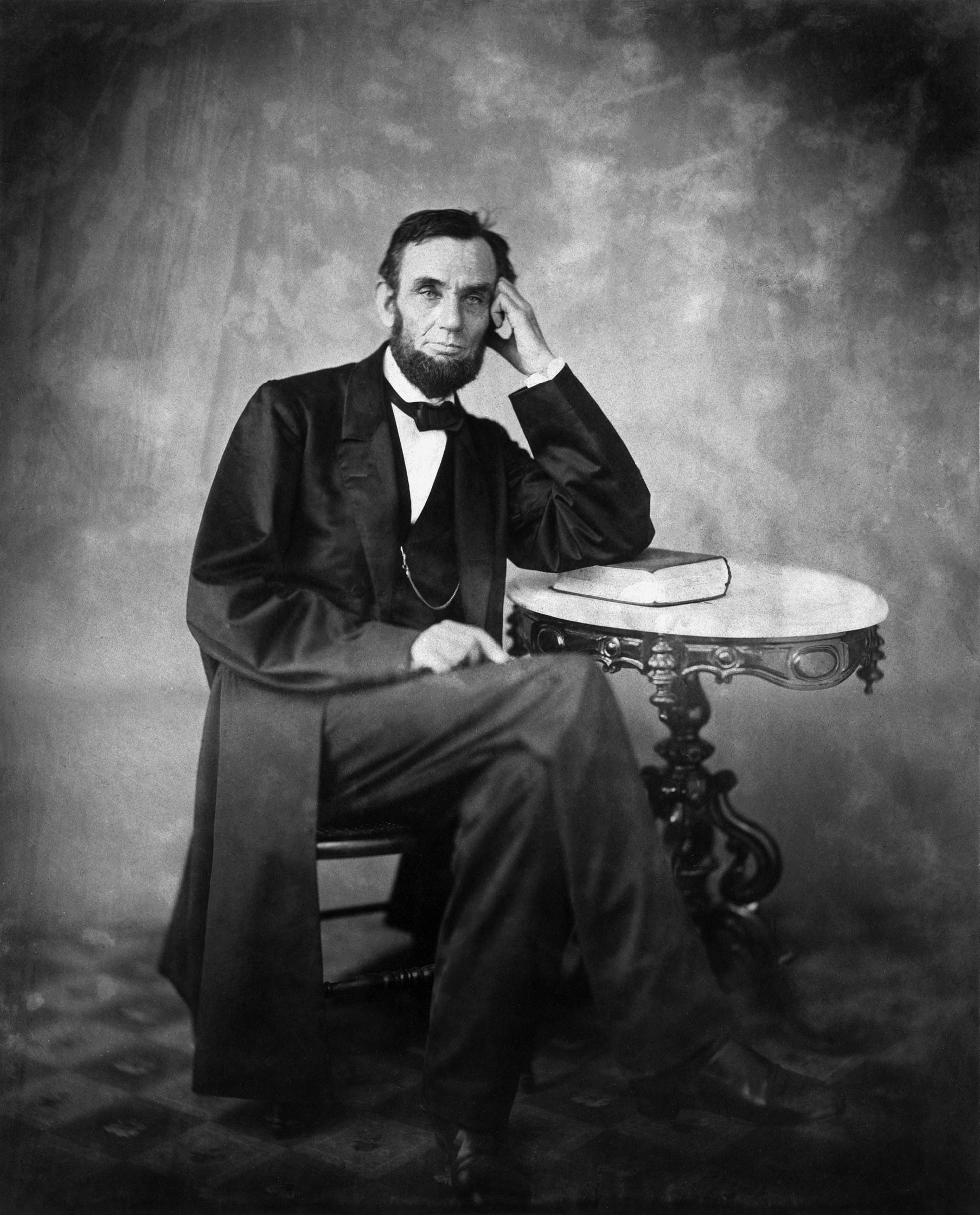

Eventually, a wise President had to decide how these issues would be addressed. President Lincoln knew that these Generals were principally correct, that elections should not be contaminated by the enemies of the Union. However, he also knew that “because the military being, of necessity, exclusive of judges as to who will be arrested, the provision [of military inspection of voters and arrests at polls] is liable to abuse”. And so, Lincoln revised general orders to ensure that the military was used only to “prevent all disturbance and violence” at polling places.

Perhaps what stands out most about Lincoln’s extraordinary order of November 2, 1863 is not his understanding that the military could be abused to influence elections, but that he was willing to let all men, even those that had opposed them at Gettysburg, vote freely and without influence. His words stand as a reminder of the importance of the integrity of the electoral systems:

“In this struggle for the nation’s life, I cannot so confidently rely on those whose election may have depended on disloyal votes. Such men, when elected, may prove true, but such votes are given them in the expectation that they will prove false.”

None of us can rely on candidates who are elected through interference and subversion. Our enemies seek to influence our elections with the expectation that the results will prove false for the health and well-being of our country and our citizens. This is an attack on our nation’s security. A top priority of the state and federal election officials should be to ensure that our enemies are prevented from influencing the electorate through subversive physical or virtual presence in our elections. And a top priority of the electorate should be to demand assurance from those same officials that our elections can take place in a free and fair manner.

~ Quotes are from Abraham Lincoln’s Letter to Governor A.W. Bradford of Maryland, November 2, 1863.

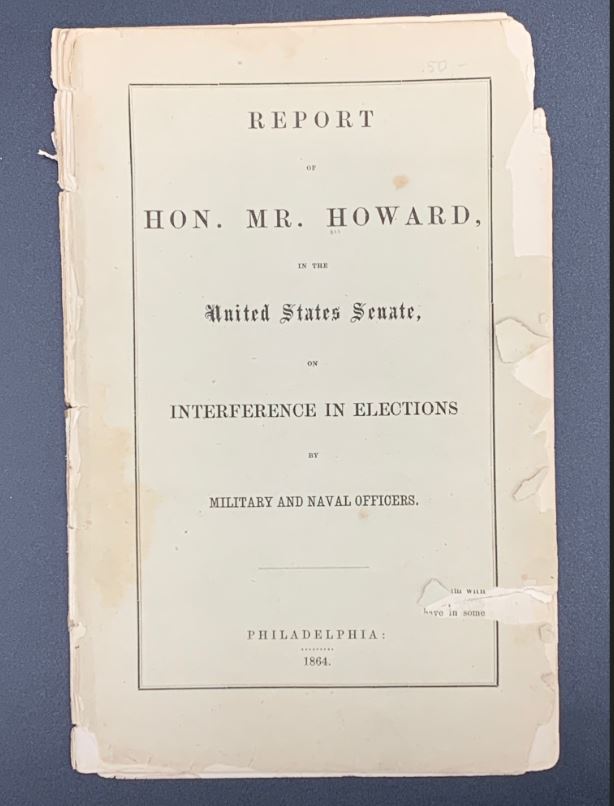

For more information about the 1864 debate on interference in elections, you can read the report delivered to Congress by Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan at the Library of Congress website.

I haven’t written in this blog for sometime due to obligations and other writing for publication. However, I was compelled to write a piece about effective posting in an online course. I have taught dozens of courses online, and graded hundreds of assignments, and the following is just some advise that I wish I could have received as an online student. Advice that is provided strictly as an account of my personal thoughts and recommendations for effective submission of assignments in an online educational environment.

I hope that my students, and other students as well, find it useful.

Dear Online Homeland Security Students,

After 5 years of instruction in the Homeland Security Program at Concordia, I have read hundreds responses to discussion board and weekly assignment questions. Yet, I am often surprised and delighted by students who introduce new and exciting ideas or angles on these interesting topics – causing us to reflect on the wicked problems of the complex and challenging homeland security and emergency management disciplines.

At times, however, whether because of the demands of life or work or the challenges of scholarship, students miss the opportunity to truly reflect on the issues that we discuss in class, and simply write a comment or two in passing, missing the opportunity to learn and discuss critical issues with their colleagues. This hurts not only that student’s experience, but that of their peers, who are deprived of their unique insight and experience. We have so many professionals and veterans in this program who, in one way or another, have been involved with homeland security and emergency management for many years, and have much to share. We need those insights as a community of learning!

To aid and encourage my students, I have developed a guide for getting the most from your online experience in the homeland security and emergency management program. I believe that by following these six (6) simple aids, you can enhance your learning opportunities, expand your enjoyment of the course, and improve your point totals as well!

Six Recommendations for Responding to Essay and Topical Discussion Assignments Online

1. REFLECT

We are community of learners. The reason why education works in a community of online learners is because we bring our individual experiences to the community and share them with others, forming a reflective “circle of trust” that enables each of us to gain something that would not be gained without the community. Lectures don’t do that, learning in community does. This is not new. John Locke, as quoted by Alexander Ireland in The Book-Lover’s Enchiridion said:

“Education begins the gentleman, but reading, good company, and reflection must finish him.”

So often, we jump into Blackboard, jump into the week, read the questions and start typing a response. When we do this we sometimes miss the contextual importance of the question, which is often the whole point of the discussion!

As an alternative, try reading the question the night before you respond, or in the morning before the drive to work, and REFLECT on the question and what you know about the topic. By doing so, you can allow your mind to begin forming a response without the need to write. Allow your mind to wander into related issues and begin forming connections that you can bring to your response when you sit down to write.

2. RESEARCH

Before you respond to an assignment or discussion, and armed with the reflective connections that you made as you thought about the topic, look for existing literature on the subject. Often, our reflective ideas are supported or challenged by the work of colleagues, journalists, and scholars who are also thinking about these issues. Maybe your ideas and connections will be altered – that is ok! You have not written yet, and it is fine if you are influenced by the ideas of others. In the end, your response should be a summation of your unique experience and knowledge combined with the ideas and insights of others.

Remember that the ideas of others are an important result of their own hard work and dedication to the discipline of homeland security. As such, and out of respect that we ourselves deserve in kind, we give them credit for their hard work by noting in the text where we allude to their work, and we tell our colleagues where to find their work by including a reference. Citations and references are how we share and support the efforts of the learning community and further the discipline and its effectiveness.

3. RESPOND

When it is time to write a response, be sure to gather your thoughts, ideas and research into a coherent and concise response to the question or topic at hand. Often, students fail to directly address the question in their response. For instance, if you are asked to RESPOND to the question of whether drone strikes on US citizens abroad is legal, than you should take a position that it IS legal, or IS NOT legal. Your essay or response should be clear and supported by sources of information that bolster your contention. If, alternatively, the question is whether drone strikes on US citizens abroad are morally defensible, that is a different question, and that is the question that must be addressed, regardless of legality.

I am often asked how to format such a response, and in reply I typically recommend that, in the absence of a structure that you prefer or have found better supports your unique response, the following structure seems to work in many cases:

Introduction – a concise opening paragraph where you articulate your response to the question and the basis for your unique approach to responding to the issue or question raised. First sentence is important to capture the reader’s attention and set up the response;

Support Paragraph #1

Support Paragraph #2

Support Paragraph #3

Conclusion – A concise paragraph in which you summarize the three aforementioned paragraphs, bring the reader to a focused conclusion and articulate how your solution or response to the question is the best and most magnificent idea that anyone has ever had in the history of human scholarship.

In general, this structure provides a good outline for responding to essay-type assignments. Assuming that each of these bullets is a moderately-sized paragraph, you will end up with a response of about two (2) double-spaced pages, or around 500 words. A condensed version of this is appropriate for discussion board responses.

4. REFRAIN

In my experience there are a few common issues that occur in online writing that form a small list of things to avoid. They tend to make the responses less interesting, and have the hallmarks of a rushed, thin, and insubstantial response. Here are a few things to REFRAIN from doing in your online submissions.

REFRAIN from . . .

. . . Stating Personal Opinions ─ If you write the words “I think. . .”, “In my opinion. . .”, or “I believe. . .” you should look carefully at what you said and ensure that you are not just stating an unsupported or unrelated personal opinion. Your response should focus on what you know, not what you think you might know about a topic. Knowledge comes from experience, research and reflection, as stated above. Leave your unsolicited opinions outside the course room.

. . . Making Broad Generalizations ─ If you are tempted to write the words “all. . .” or “always. . . ” or “every. . .” you might be about to make a broad generalization, and the first question your reader will ask is “is that always true?” Please avoid broad generalizations relating to the issues and topics we discuss. It is very likely for every instance that you stated “all” or “always” there are instances where that just does not apply. It is an indication that you did not research or reflect on the topic and on your response, and you might just be stating your opinion without any contextual applicability to the discussion.

. . . Giving Unfounded Praise – So often, especially in peer responses, students are tempted to give praise to their colleagues without any reflection on whether it is appropriate. I get it! We are all in this together and we love to be positive and friendly. That is awesome! But think about it. If we are telling our peers that what they said was the best thing since The Great Gatsby and they didn’t even answer the question, we are not doing anyone any favors. Instead of giving unfounded praise, RESPECTFULLY CHALLENGE your peers. Start by asking whether or not their response RESONATES with you and your experience. If it does, why? Let them know! If it does not, why not? Tell them why you think that maybe the answer lies in another dimension of the topic.

. . . Submitting Something You Are Not Proud of – Do not hit the submit button on work that you are not proud to sign. Your responses are becoming a part of the archives of the University, and your papers could be an early manuscript of your work that people will dig up after you have won the Pulitzer Prize. Be thoughtful about what you submit. PROOFREAD your work, REVISE it before submittal, and make sure you are proud of the product. Ultimately, your work is a reflection of who you are as an individual. Make sure that your reader is left with a good impression of your scholarship, and is not distracted by sloppy, careless, and unedited writing.

5. RELIVE

…as in your experiences. I am always amazed and humbled by the diversity of experience and backgrounds that makeup the students of this program. PLEASE bring YOUR experiences to bear on the questions and topics discussed in the courses. PLEASE talk about YOUR experiences and insights. PLEASE share stories about how YOUR perspective is formed by your unique life experience. I am NOT asking for your opinions, experiences doesn’t mean opinions (see above), there is a difference. Learning is about seeing the world from another’s perspective, through the lens of another’s unique and beautiful journey through life. To the extent that you are comfortable, please share yours whenever it relates to what we are discussing, and help us learn about the world.

6. RETURN

Sometimes a response just won’t be apparent. Even after the research phase, you might not be sure what to write, or how to respond to a question. Fear not! It happens to everyone. One technique for dealing with that is to RETURN to the foundations of the homeland security enterprise. For me, foundational aspects of homeland security include things like:

Critical Thinking – What is really going on here? What is the bigger picture? What is right and wrong and how does it apply here? Who are the players and what are their motivations? Who wrote this and why? Why does it matter? When did all this happen? Why did this happen? Why is it like this? WHO CARES??

Ethical Decision Making – Is this the right choice? How are people affected? Who is making the decisions and why? What is their motivation? Does this benefit the greatest number of people? Why do this? Is this the right use of resources? Is there a good return on investment? What would I do and why?

Leadership – Who is in charge here? What are the pressures involved in making these decisions? Who gets to decide? What is their perspective? What keeps the leaders up at night? What intelligence did they have when they made that decision? Who is right?

By returning to these and other foundational aspects of our discipline, you may find the springboard into your response. Sprinkle that with some research and experience, and you’ll have a post to be proud of. Hope that helps!

For a copy of the guide in pdf form, please leave a comment with your information or message me directly and I will be glad to send it.

The term “critical infrastructure”, like “homeland security”, is broad and ambiguous. A deconstruction of phrase is not particularly helpful, as it generates more questions like “what is meant by ‘critical'” and ‘what qualifies as ‘infrastructure'”? The USA PATRIOT Act defines “critical infrastructure” as “systems and assets, whether physical or virtual, so vital to the United States that the incapacity or destruction of such systems and assets would have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination of those matters” (USA Patriot Act of 2001 (42 U.S.C. §5195c(e)). This consequence-based definition is referenced in National Infrastructure Protection Plan as well. This definition, while helpful, does little to demystify critical infrastructure as a concept.

In 2003, a large scale blackout was experienced by much of the Northeastern United States. Obviously, the electrical system is critical infrastructure according to the definition provided above. But given the reported cause of the Blackout, software, human factors and system deficiencies, these systems may also meet the definition of critical infrastructure. Their failure certainly had a debilitating impact on security, economy, public health and safety. So where does the critical infrastructure begin? Since much of our infrastructure is systems within systems, which parts are critical? The definition provides little granularity for those that care about the protection of critical systems.

At the core, the USA PATRIOT Act definition is inadequate to describe the role of critical infrastructure in society, which is a better way of thinking about critical infrastructure and key resources. At the most basic level, the definition of critical infrastructure is systems that we build to reduce our dependence on, and the effects of, the natural world. The best definition of critical infrastructure is to describe what the phrase means, and what the characteristics of CRITICAL Infrastructure are. These characteristics include the fact that most critical infrastructure are themselves systems or networks, or are critical components of systems or networks. These are interdependent with other infrastructure and their criticality is self-organized. Critical infrastructure is often reliant on other infrastructure and therefore it tends to organize itself into scale-free networks with critical nodes and links to other infrastructure.

I propose the following foundational definition of critical infrastructure:

Critical infrastructure are interdependent, organized systems that are essential for supporting and sustaining communities and their separation from the natural world.

Homeland security as a vocational paradigm is unique. Rather than being simply a field of study or discipline itself, it encompasses several major disciplines as part of its scope. This is why “homeland security” is hard to describe, and is often referred to as an “enterprise”. The complexity of homeland security extends to its fields and disciplines as well, many of which require a combination of a foundational education and job-specific training. Consequently, I am often asked about the difference between education and training, and I believe there is a difference, one worth understanding.

Education and training are sometimes used interchangeably, and when they are, some will seek to correct matters by citing proverbial guidance. For instance, one can be trained to fly an airplane without the knowledge of the physics of flight. Flight training provides the former, and aeronautical education the latter. And of course there is the example of sex education versus training. But these examples fail to consider that education can happen during training sessions, and training can occur as part of an education. So what is the difference? And why should it matter?

The key to understanding the difference lies in an understanding of learning objectives, and cognitive domains. While this sounds difficult, it really isn’t.

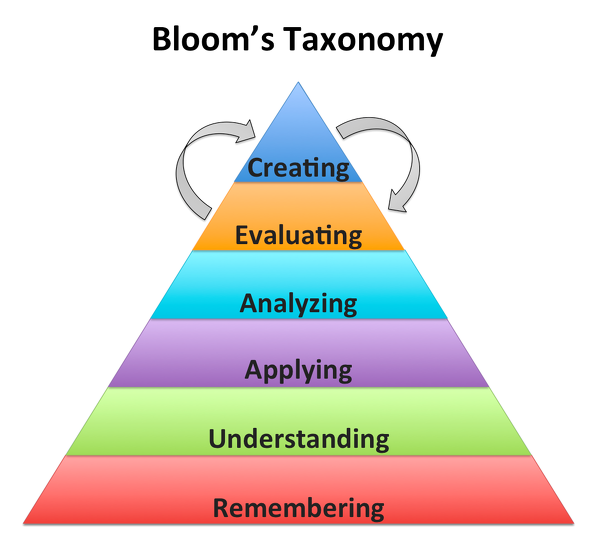

The learning objectives of training are typically framed in a way that informs students about a specific topic. This may involve an individual piece of equipment, a unique method, or a complex process. Often the scope of training is limited, and a demonstration of competency is sufficient to judge the efficacy of the training process. The goal of training is knowledge transfer, from trainer to trainee, and demonstrated comprehension on the part of the trainee. The result is what I will call “applicable knowledge”. The student is able to apply the results of the training in a specific way to make them more effective at whatever they might be doing – putting out fires or saving someone from choking. Applicable knowledge is represented by the first three levels of Bloom’s Learning Taxonomy – Knowledge, Comprehension and Application.

The purpose of education is somewhat different. The learning objectives are (or should be) aimed at providing what I will call “foundational knowledge”. Unlike applicable knowledge, foundational knowledge is transformational. It supports the student by providing theoretical bases for the way things are, transforming their understanding of the world, at least a part of it. Foundational knowledge is represented by the last three levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy – Analysis, Synthesis and Evaluation. Armed with foundational knowledge, a student should be able to create his or her own unique method or complex process based on their theoretical knowledge of the way things are.

It is important to note that foundational knowledge can be a result of training. For instance, a course on a specific risk analysis methodology could include a module on the history of risk evaluation and assessment that explains why risk assessment is important and how it changed the world. The training module on the history of risk adds foundational knowledge to the student’s repertoire, while the hands on training in the method arms the student with a tool for risk assessment application. Both are important and essential to the success of the student. The educational component adds richness to the training.

In the same way, an educational course of study can equip students with practical tools. A college-level course on risk assessment could include a module on a specific risk assessment methodology. In this way, the student leaves the course with not just the “why”, but the “how” as well. The training in the specific method, in this way, adds richness to the educational course of study.

The effective and deliberate combination of training and education in a course of study can be an indicator of sound instructional design. As such, an understanding of the distinction is important.

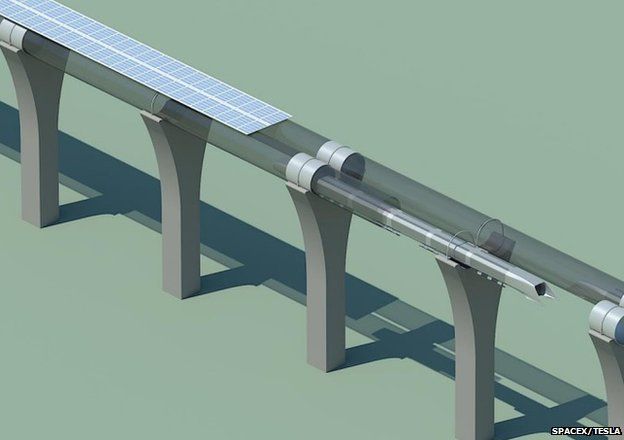

In May, a test of Elon Musk’s Hyperloop transportation concept was conducted in the Nevada desert. While much of the discussion around the Hyperloop’s potential has been in the area of cargo transport, the project has always been envisioned as a people mover. In 2013, when the idea was initially released, there was a public comment period. The initial submittals outlined the Hyperloop concept, including the structural components like the stanchions or “pylons” that support the elevated track and low pressure tube. On August 13, 2013, I submitted the following commentary for the consideration of those working on the project. My comments outline some of the security issues that the new transportation infrastructure brings to mind. Seldom do security professionals have the opportunity to consider the security of critical infrastructure systems BEFORE they are built! I never received a response, so I place my comments here for posterity and invite comment and discussion.

| to: | hyperloop@spacex.com, hyperloop@teslamotors.com |

||

| date: | Tue, Aug 13, 2013 at 9:17 PM | ||

| subject: | Security Considerations Impact Efficiency of Pylon System | ||

Elon and Companies,

Increasingly, critical infrastructure is becoming the battleground for a global power struggle to see which country (or collective) will emerge as the superpower of the digital age. The United States’ significant conventional military superiority remains a reality. But our enemies seem willing to concede the might of the US military in favor of anonymous, targeted cyber attacks on critical infrastructure and key resources. Today’s New York Times story on the activity of Russian naval vessels near undersea cables reminds us that there are many vulnerabilities in the global information infrastructure.

As in wars past, a focus of the next war will be the crippling of infrastructure. The difference is that this can now be done remotely, without physical invasion, from cyberspace, or from international waters. It can be done via drones. It can be done by people that don’t exist, via groups you’ve never heard of, from places you’ll never find. And it won’t be done to fortresses or government compounds built for resilience, but to private corporations and municipal utilities built for profit and service.

So what can we do to better protect critical infrastructure? Here are five ideas:

- Provide grants to critical infrastructure owners and operators, directly, to protect their networks.

- Restore and fund the Buffer Zone Protection Program.

- Enable DHS Protective Security Advisers to initiate projects based on the results of vulnerability assessments they conduct, especially when they find critical vulnerabilities.

- Conduct random penetration testing of US infrastructure to find vulnerabilities and report them.

- Initiate a nationwide campaign to raise awareness of our vulnerabilities and assist the public in reporting threats to critical infrastructure.

We need to think about what, realistically, can be done that is MEASURABLE.

This article that appeared in Tech Crunch this week reminded me of a post that I published here in 2013. The changing landscape in cyberspace and the issue of statecraft in cyberspace is a subject of this article, and lies at the heart of the issue that I find interesting. That is, what is missing with regard to the defense of the homeland in state-sponsored cyber war? I think it may be the link between government and private-sector infrastructure, or a diplomatic realm for discussing cyber activities, but I am not sure – there are likely several things. I am not sure I captured them in 2013, but I continue to find the issue fascinating. Your comments are welcome.

Here is a reblog of the earlier article:

On the Need for a New Diplomatic Dimension for Cyberspace – Originally published in September 2013

In the wake of Mandiant’s APT1 report and in the midst of the Edward Snowden affair, it has become increasingly apparent that cyber diplomacy is something different than traditional international statecraft, and that the current diplomatic model is not sufficient. Countries of the world, including and especially the United States, are attempting to manage cyber-related issues via existing diplomatic fora, using existing diplomatic resources. The results are predictably disappointing, since cyberspace rarely conforms to the traditional business models of the 20th Century and before.

In June (2013) the State Department issued a press release to announce the United States’ conformation to the findings of the United Nations’ Group of Governmental Experts on Cyber Issues regarding the effective applicability of the UN Charter and international law to cyberspace. Little attention was paid to the announcement, but its significance should be noted. The overlay of existing international law and pre-cyber landscape charters is convenient (easy), but will not conquer the wicked problems of today and certainly not tomorrow. The ability to be engaged in a cyber war with a country in the virtual world while simultaneously maintaining “normal” diplomatic relations in the “real world” cannot be addressed by current standards. This is the state of affairs today as the Mandiant report illustrates. Yet, as normal diplomatic procedures require careful rapprochement,

diplomats dance the dance and each party avoids discussing the issue directly while business interests are drained of their intellectual property like a water park after Labor Day.

The answer is not the United Nations or governments, which is why the problem may never be solved adequately in the current generation. What matters in the networked world is data and infrastructure, and threats and vulnerabilities. Nations are data owners (or at least holders), but so are companies, groups and individuals (like Snowden (he’s currently a holder)). Nations also own infrastructure, but so do the private sector entities which own, for instance, the end user interface and telecommunications infrastructure. A forum must be established where these stakeholders can operate on more of an equal footing, where countries are considered stakeholders just like the companies that own the networks on which they ply their trade. The solution lies in a new dimension, one that is not formed in the crucible of the United Nations but is rooted in the networked world in which it must operate. The management of our global network must be something complex and wonderful like the internet itself. Where the power is held in the hands of those with the knowledge, information and interest to influence the direction of the global network. It must be dependent on self-organized criticality.

A continued insistence on the application of current diplomatic technology in cyberspace is likely to diminish the progress of the human race. The evolution of the networked human will be slowed by the Dickensian chains of nation-based world order. The so-called “Arab Spring” provides evidence that the youth of the world with access to today’s technology cannot be satisfied when burdened by the constraints of national governments unwilling to free them to take full advantage of a networked Earth. While the former generation’s power brokers attempt to make these disturbances about political and religious issues (because that is what they know), the heart of the issue is really growing pains. We are evolving as a species faster than our organizational structure will allow.

A positive first step would be the recognition that national sovereignty is not a major factor in the future paradigm, and that the United Nations, which has failed to act promptly and responsibly to address conventional issues, is simply not equipped to manage the complexity of a networked solar system.

Homeland security is not a precisely-defined discipline. Rather, it tends to encompass issues that relate to risks to the people, stability and infrastructure of the United States. Consequently, when an issue arises that is associated with these risks, a thought-provoking exercise for scholars in homeland security is to note the role of homeland security professionals, and the Department of Homeland Security, in addressing the issue. Such an opportunity is presented with today’s announcement of a national strategy for the promotion of honey bees and other pollinators.

Over the past several years, entomologists have noted a decline in the populations of honey bees and other pollinators. These declines are worrisome because of the role pollinators play in the food supply. Additionally, the global decline in certain insect species could indicate a larger problem the magnitude of which has yet to be discovered. These concerns have reached the White House.

In June of 2014, President Obama released a Presidential Memorandum calling for the development of a strategy to protect and promote honey bees and other pollinators. Section 1 of the memo outlined the departments involved, and the Department of Homeland Security was conspicuously absent. Yet DHS maintains the National Infrastructure Protection Plan, the goal of which is to “identify, deter, detect, disrupt and prepare for threats and hazards to the nation’s critical infrastructure”, and among the identified critical infrastructure sectors is Food and Agriculture.

So what can DHS bring to the issue of bees and butterflies? The answer is the resilience model. While the leaders of the task force – the Department of Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency – will undoubtedly focus on the causes of pollinator decline, the improvement of habitat and the support of growers and beekeepers, someone needs to focus on resilience in the face of declining pollinator populations. DHS has programs in place for mobilizing readiness in the face of disasters, and by many accounts, the decline of the honey bee is disastrous.

In 2014, DHS announced its intent to focus on climate change, recognizing the need to prepare for the resulting impact on homeland security. At the time, a senior DHS official was quoted in Reuters as saying “increasingly, we’ve moved not only from a security focus to a resiliency focus”. If this is true, honey bees are a homeland security issue.